Moments In Music: The Folk Revival And Stuff, Part I

[I’m a bit obsessed with learning where things come from, how things started, and how things became the way they are. This applies to art, music, history, life…you name it. Of the infinite possibilities that exist, how did this particular one come to be? (This is probably why I love the movies Run Lola Run and Sliding Doors. Just sayin’).

I thought I’d write some posts about where particular musical and art movements originated, and how they came to be. This is something I’ll probably do over an extended time, alternating with more practical art and music posts.

I decided to begin with the folk music revival of the 1960s, a movement that influenced a huge amount of songs and artists in the six decades that have followed. This is my very condensed, whirlwind tour of the music that converged to become Bob Dylan, John Lennon, Donovan, Joni Mitchell, and a ton of musicians that followed. There’s so much to say it may take two posts. Or more. But here we go.

All songs belong to the artist and their publisher: I share them here with respect].

The Folk Revival of the 1960s and where it came from, Part I

Bob Dylan. John Lennon. Donovan. James Taylor. To some extent, household names. I’d venture a guess that even if you are under the age of 20, you know a couple of these names, and have heard their songs. They are some of the names that define the very turbulent and transformative 1960s popular music scene, and in particular, the Folk Revival of the ‘60s, which became the soundtrack, to a large extent, of the anti-war movement, the Civil Rights movement, the Feminist movement, and a dozen other attempts at sweeping social change.

But these artists and their music did not simply appear: they were a product of their influences and of their lives. I want to take a rather meandering look at how the “perfect storm” of ’60s folk music came to be, and at how it has influenced a ton of styles and sympathies that have come since.

Peter Paul and Mary in 1965, singing Bob Dylan’s song “Blowin’ In The Wind.” This band and this song were typical of the topical folk songs of the era, which challenged established social norms like race inequality, war, and the class system.

To begin, I think it’s important to define ‘folk music.’ In essence, folk music is the traditional music of any country or ethnic group: Irish folk music, French folk music, Lithuanian folk music, etc. Why the term folk music? Once upon a time all music was just music. But starting around the Renaissance (1400-1600 AD throughout Europe, earlier in Italy), wealthy individuals, and the institution of the Church, began to hire musicians to entertain during functions or services; musicians skilled at creating new music began to compose for those events. With the development of new instruments, groupings of musicians playing together and the compositions they played became more and more complex. By the Baroque era (1600-1750) musicians had formed the groupings we now call orchestras and choirs, and composers like Beethoven and Bach had emerged, patronized by wealthy lords and kings, and by the Church.

To differentiate this composed music from the music of the common folk, the distinctions ‘classical music’ and ‘folk music’ were made. Folk music was, simply, the music that regular people (the folk) continued to play as they had since time first began. Folk music preserved ancient instruments, scales and styles, and at the same time, evolved with the introduction of new instruments, new languages, and new musical influences.

The folk music that arrived in North America with the first waves of settlers was Irish, English and Scottish folk music, and West African folk music. Over several centuries, these styles blended to form the music we know today as Appalachian (also called Old Timey), Country, Bluegrass and Gospel. These styles became standards in the eastern U. S., and as they traveled west with settlers they mixed with Spanish and Mexican styles to become Western or Cowboy music.

Above: The Carter Family performing “Wildwood Flower.” The Carter Family were one of the most popular folk/Appalachian acts of the 1930s and 1940s, and were heard on the radio consistently. This style of music was the blend of Irish, Scottish and West African that came to be known as American folk, or Appalachian Old Timey. Below: Uncle Earl performs “The Girl I Left Behind Me.” Uncle Earl is a contemporary Old Timey band doing traditional songs that would have been common at any saloon or shindig in 1800s Appalachia.

Depressed Musicians

Let’s jump way ahead, to the early twentieth century (have no fear: I’m going to make up that whole leap in time when I talk about Blues and Jazz in a future post). In 1929, America entered a pretty rotten era called the Great Depression. It was also called the Dust Bowl era in the Midwest, owing to a major drought that caused catastrophic dust storms. In a word, this era sucked.

During this generally crappy time, when people traveled extensively seeking work, most people were poor and desperate. If you could play guitar or banjo, or even just carry a tune, you might be able to make some money. So traveling musicians were common, playing folk style music, and adding to the folk legacy by writing songs about the hardships of the era. A lot of those songs are still played today.

Harry McClintock’s recording of “The Big Rock Candy Mountain,” a depression era hobo song about a fantasy land where hobos live in luxury. The recording was used in the film O Brother Where Art Thou.

One type of Depression era traveler was the hobo. Hobos often gathered in hobo camps, where they traded songs. They rode freight trains to get from one place to another, and feared police and “bulls,” railroad agents who would drive them off of cattle cars, often violently. Many folk songs were written and carried along by hobo musicians.

Modern street musicians in New Orleans continue to play 1930s hobo songs; many still live the hobo lifestyle, hopping trains and staying in “squats” or abandoned buildings (the musicians above do not stay in squats… they actually pay rent. But they do play hobo songs).

One of the most influential musicians to come out of the Great Depression was Hudie Ledbetter, best known as Lead Belly (or Ledbelly). Living a Depression era life full of travel, sorrow and stints in prison, Lead Belly became the musical voice of that era. His repertoire included folk songs, slave songs, field hollers, Underground Railroad songs, labor songs, and songs about life during the depression. His music has been covered by acts that include Bob Dylan, Credence Clearwater Revival, and Nirvana.

Above: a recording of Lead Belly singing at a concert organized by the Lomax family: Below: ’90s Grunge band Nirvana play a Lead Belly song, “Where Did You Sleep Last Night.”

Another Depression Era great was Woody Guthrie. Known as “the Dustbowl Troubadore,” Guthrie traveled with displaced workers from Oklahoma to California during the 1930s, learning folk songs and writing political songs, especially about class inequality and the growing movement to unionize corporate workers. Guthrie wrote so many now-famous songs it would make your eyeballs hurt: his most famous song is probably ‘This Land Is Your Land,’ which was being taught in schools when I was a kid, and most likely still is.

Above: Woody Guthrie shown with his signature guitar, on which is painted the slogan ‘This Machine Kills Fascists.’ Below: the Grateful Dead performing a Woody Guthrie song.

It’s probably a good idea to mention that Lead Belly and Woody Guthrie both owed a bit of their celebrity to a man named Alan Lomax. Lomax was like the Pharrell Williams of the mid twentieth century. Along with his father, John A. Lomax, he discovered, produced and publicized hundreds of folk musicians in America, Ireland, England and the Caribbean, and amassed a vast collection of folk songs (his collection was acquired by the Library of Congress in 2004, becoming one of the largest collections of folk music in the world). Lomax hired both Lead Belly and Guthrie at various times, and organized concerts and radio appearances for both of them. Most music stores still carry music book collections of folk songs by senior and junior Lomax.

Lead Belly and Woody Guthrie playing together on a radio show in 1940.

Folk Music and Organizing

Life was tough during the depression, partly because a lot of people needed jobs, so industries could hire workers for very little money, and expose them to horrible, dangerous working conditions. If one person didn’t want to work under conditions like that, there were hundreds to take their place. As the era wore on, workers began to seek organizations that would protect them: labor unions. But organizing unions was no picnic. Labor bosses did not want unions, because they’d have to pay more and give workers benefits: they didn’t much care for that. Corporations would hire “goons,” strongmen to beat and even kill union organizers.

Getting the word out to workers was a major part of efforts to organize unions: union organizers depended greatly on folk musicians. New and old folk songs inspired workers to fight for their rights, and to demand fair treatment from corporations. It was the first era of social reform led by folk music.

The Old Crow Medicine Show, a contemporary Old Timey band, singing a union organization song from the 1930s.

One of the great union activist folk musicians was Joe Hill. A Swedish immigrant and migrant farm worker, Hill united workers with folk music, proving the power of this medium to organize people. Though Hill died early in the union movement, in 1915, his songs were sung by union organizers and workers of the 1920s and 30s. Both Bob Dylan and Phil Ochs had songs that referenced Joe Hill, and tons of musicians have recorded songs Hill wrote. Horror author Stephan King named his son after Joe Hill (Joseph Hillstrom King).

Folk singer and political activist Joan Baez sings about Joe Hill at Woodstock in 1969.

Greenwich Village

The power of folk music to draw people together around a cause was a lesson not lost as the 1950s began. The burgeoning beatnik movement, a movement that eschewed participation in the consumerist culture of the newly formed suburbs, gained a great deal of momentum from folk music acts. The movement had a huge following in New York’s Greenwich Village (not a separate village, but an area of downtown Manhattan). Italian immigrants in the 1830s had created a coffeehouse culture there, and in the 1950s that coffeehouse scene found new life in the form of poetry and folk music, often about consciousness exploration and social inequality.

Greenwich Village seen from Washington Square, circa 1960.

The great musical act of 1950s Greenwich Village were The Weavers, a band that was formed by Pete Seeger and Lee Hayes, who wrote such songs as “So Long It’s Been Good To Know You,” along with Fred Hellerman and Ronnie Gilbert.

Shit got real for the Weavers in the early 1950s, during the McCarthy anti-communist era. McCarthy was a U. S. senator who decided that enemies of the government were lurking everywhere, especially in the entertainment industry. His blacklisting of musicians and actors destroyed a lot of careers. The Weavers were accused of being communists, and both Hayes and Seeger were forced to testify before the House Committee On Unamerican Activities. Both musicians were blacklisted, and lost their recording contracts. This caused the Weavers to become more political, singing about the injustice of the blacklists, unfair labor practices, and about racial inequality.

The Weavers in the 1950s, playing a tribute to Lead Belly. Pete Seeger is on banjo.

Pete Seeger’s appeal widened greatly in the 1960s when he began hosting television shows about folk music, featuring Blues Musician Reverend Gary Davis and other noted folkies.

Which brings us to the early 1960s in Greenwich Village, again. Hard on the heels of the McCarthy anti-communism era came American involvement in the Viet Nam civil war. While most Americans simply saw this as another military action, a growing movement of beatniks and students felt this was an unjust war, and began speaking out. One anti-war weapon was, you guessed it, folk music.

The 1950s and early 60s was an era of great change in America: for one thing, millions of soldiers had recently returned from World War Two, and just a few years later, the Korean conflict. After being in horrible, soul-shattering wars, these soldiers all had the impulse to live “normal” lives: get married and get a nice house, a demand supplied by the development of rural lands to build millions of new homes in a semi-rural, semi-urban environment: the suburbs. Marked by conspicuous spending and the desire for security that came after years of war, the suburbs saw the growth of a new middle class in America: it also saw the birth of a whole lot of babies. In fact the 1950s is known as the Baby Boom era.

Because of efforts like the G. I. Bill, which gave veterans and their families money for continued education, something that happened during the Baby Boom was that a lot of people went to college. Many, many new college students were the first in their families to attend college; college education became an expectation not only for veterans, but for their families (many children of vets went to college under the G. I. Bill). By the early 1960s, an entire generation was going to college, rather than going into military service or industrial jobs straight out of high school.

What does this have to do with rock and roll, you’re asking me…. The U. S. government was accusing many of its citizens of being communists, and therefore traitors; the government was also getting involved in yet another war, and had begun drafting teenagers into the military. Millions of young adults were getting a higher education than ever before, which allowed them to learn about and consider events in the world around them. Suddenly young people found that they were dissatisfied with the way things were: racial issues, war, class struggle and political leadership all came under scrutiny on the college campus.

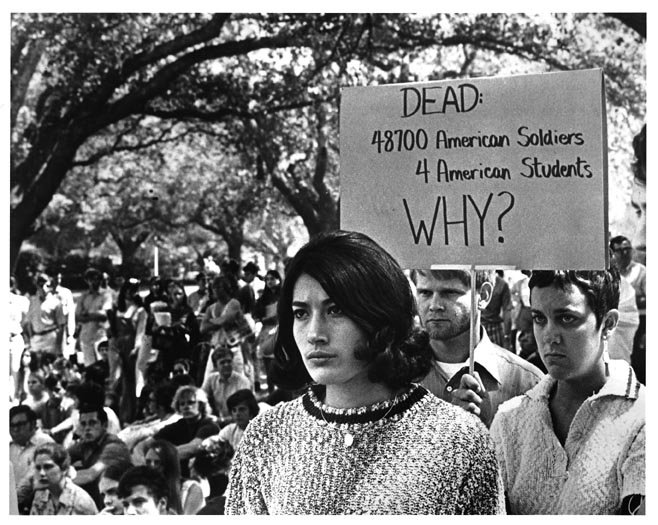

1960s anti-war protest.

And that was the magic moment, musically speaking, when a couple of voices would change the world forever.

Which we will discuss in Part II. Stay tuned!